Are you fascinated by the history of Japan? If so, you’ll be interested to know that Japan’s history spans thousands of years and is filled with rich and intriguing periods. In this post, we provide an overview of Japan’s major historical periods, from the Paleolithic era to the present day. Join us on this journey through time!

The origins of Japanese history

Japan’s historical periods are classified based on the rulers, dynasties, or distinct cultural and social characteristics of each era.

In the beginning, Japan was inhabited by hunter-gatherers before the first agricultural communities settled on the islands. The Heian period marked a significant cultural blossoming with strong Chinese influence. The Edo era was characterized by political and economic stability under the Tokugawa shogunate, while the Meiji Restoration ushered in modernisation and westernisation.

While Japan’s history has its roots in prehistory, the first well-documented periods began with the early imperial dynasties. The Yamato and Portico dynasties were instrumental in establishing the emperor’s power and laying the groundwork for a centralised government.

Paleolithic period in Japan (30.000 b.C. – 14.000 b.C.)

The Paleolithic period in Japan marks the earliest human presence in the archipelago, lasting until the beginning of the Jōmon period period. During this time, the inhabitants were nomadic hunter-gatherers who adapted to their environment and climate. They used carved stone tools such as axes, scrapers, and arrowheads for hunting animals and gathering fruits and roots. Archaeological findings of hearths, bones, and shells indicate that they also practiced cooking.

Jōmon period (14.000 b.C. – 300 b.C.)

The Jōmon period is one of the longest and most diverse periods in Japanese history. It is known for the development of pottery, characterised by the distinctive rope-patterned decorations. Jōmon pottery was used for various purposes, including cooking, storage, and rituals.

The Jōmon people were primarily hunter-gatherers who relied on fishing, hunting, and gathering wild plants. They lived in small, semi-nomadic communities and had a profound connection with nature. They crafted tools and ornaments from natural materials like stones, bones, antlers, and shells.

Some Shinto myths suggest that the Japanese imperial family originated during the Jōmon period.

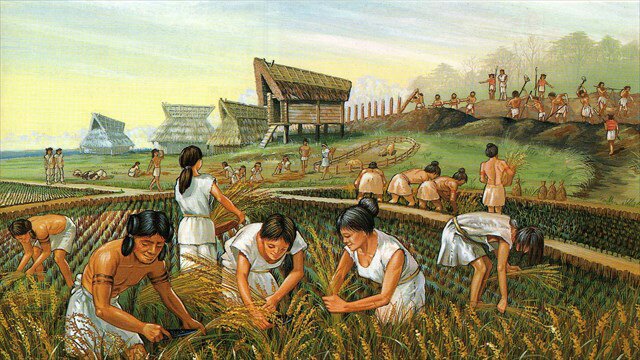

Yayoi period (300 b.C. – 300 a.C.)

The Yayoi period marks the beginning of significant continental influence in Japan, particularly from China and Korea. This era is characterised by the development of rice agriculture, bronze and iron metallurgy, and the formation of tribal states. Yayoi pottery, simpler and more functional than Jōmon pottery, was primarily used for storing grain and water.

The Yayoi people lived in hierarchically organised farming villages with a ruling elite and a warrior class. They practiced religious rituals related to rice cultivation and ancestor worship.

This period is also known for the legend of Yamatai-koku, a mysterious kingdom ruled by Queen Himiko.

Kofun period (300 – 538 a.C.)

The Kofun period is named after the large mound-shaped tombs (kofun) built for the political and military leaders of the time. These tombs contained grave goods such as weapons, jewelry, mirrors, and clay figures called haniwa.

This period is divided into two sub-periods: the Asuka (6th-7th century) and the Hakuhō (7th-8th century). The Asuka period saw the introduction of Buddhism, writing, the calendar, and the legal system from China and Korea. Imperial power was consolidated under the Soga, Mononobe, and Nakatomi clans. During the Hakuhō period, significant political, administrative, and cultural reforms inspired by the Chinese model were implemented, including the Taika Reform and the Taihō Code.

Asuka period (538 – 710 a.C.)

The Asuka period was marked by the introduction of Buddhism to Japan, which significantly influenced the country’s art, architecture, culture, and politics. During this time, the Yamato government established itself as a centralised monarchy and adopted the court-rank system.

The capital was located in Asuka-kyō, in present-day Nara Prefecture. This period also saw the first diplomatic and cultural contacts with China and Korea, as well as conflicts with the Silla kingdom.

Nara period (710 – 794 a.C.)

The Nara period is notable for establishing Japan’s first fixed capital in Nara, modeled after Chang’an, the Chinese capital of the Tang dynasty. Nara housed the imperial palace, Buddhist temples, government offices, and the residences of the nobility. This period was also a time of cultural flourishing, producing literary works such as the Kojiki, Nihon Shoki, Man’yōshū, and Genji Monogatari.

Buddhism became the official state religion, and grand temples like Tōdai-ji, which houses the Great Buddha of Nara, were constructed. However, the political power was undermined by the influence of monks and landowners, prompting the capital’s move to Heian (modern-day Kyoto) in 794.

Heian period (794 – 1185 a.C.)

The Heian period is often regarded as the golden age of Japanese culture, marked by the development of unique artistic and literary styles distinct from Chinese influences. The imperial court in Heian-kyō (modern-day Kyoto) was the center of political and cultural life, where nobles engaged in poetry, music, calligraphy, and aesthetic refinement.

This period is divided into two sub-periods: Early Heian (9th-10th century) and Late Heian (11th-12th century). The Early Heian period saw the consolidation of the ritsuryō system, which regulated administration, taxation, and social hierarchy. Additionally, the regency system (sesshō) and shadow government (sekkan), which allowed the Fujiwara clan to wield real power, were also established. The Late Heian period witnessed the decline of imperial authority and the rise of military clans (bushi) vying for territorial control.

The conflict between the Taira and Minamoto clans culminated in the Genpei Wars, ending the Heian period and ushering in the Kamakura period.

Kamakura period (1185 – 1333 a.C.)

The Kamakura period is defined by the establishment of Japan’s first military government or shogunate, led by the Minamoto clan from the city of Kamakura. The shogun was the de facto ruler of the country, while the emperor held a symbolic role.

This period is also divided into two sub-periods: Early Kamakura (12th-13th century) and Late Kamakura (14th century). The Early Kamakura period was notable for the successful defense against the Mongol invasions led by Kublai Khan. It also saw the rise of new Buddhist schools such as Zen, Nichiren, and Jodo. The Late Kamakura period was marked by political and social turmoil due to famines, epidemics, natural disasters, and peasant uprisings. This unrest led to the shogunate losing its legitimacy and being overthrown by an imperial restoration under Emperor Go-Daigo.

Kenmu period (1333 – 1338 a.C.)

The Kenmu period was marked by Emperor Go-Daigo’s efforts to restore imperial power and end the military rule of the shoguns. The term “Kenmu” means “new policy”, reflecting the emperor’s reform plans aimed at strengthening central authority and administration.

However, the Kenmu period concluded with the failure of the imperial restoration and the rise of a new shogunate led by Ashikaga Takauji, which ushered in the Muromachi period.

Muromachi period (1338 – 1573 a.C.)

The Muromachi period is named after the district in Kyoto where the shogun Ashikaga Takauji established his residence after overthrowing Emperor Go-Daigo. This period is divided into two sub-periods: the Nanboku-chō (1336 – 1392) and the Sengoku (1467 – 1573).

During the Nanboku-chō, a civil war erupted between two rival imperial courts: the Northern Court, supported by the Ashikaga, and the Southern Court, loyal to Emperor Go-Daigo. The war concluded with the unification under the Northern Court. The Sengoku period was characterised by political fragmentation and intense feudal warfare among warlords, or daimyō, each striving to unify Japan under their control.

Despite the civil war, clan conflicts, and economic crises, the Muromachi period was also a time of cultural flourishing. Zen Buddhism, painting, Noh theatre, and the tea ceremony experienced significant development during this period.

Azuchi-Momoyama period (1573 – 1603 a.C.)

The Azuchi-Momoyama period marked a pivotal era in Japanese history, transitioning from the age of warring states to the beginning of national unification under the shoguns. This period is named after the castles built by two prominent military and political leaders, Oda Nobunaga and Toyotomi Hideyoshi.

Azuchi Castle, situated on the shores of Lake Biwa, was Nobunaga’s residence and command center. Nobunaga succeeded in subduing most of the feudal lords and established a centralized government. Fushimi-Momoyama Castle, located south of Kyoto, was the fortress of Hideyoshi, who completed Nobunaga’s work by pacifying the entire Japanese territory. Both castles were notable for their imposing architecture, rich decoration, and dual functions as defensive structures and symbols of power.

During this period, Japan experienced significant social, economic, and cultural changes. These included the growth of domestic and foreign trade, the development of cities, the spread of Christianity, the flourishing of arts and literature, and the influence of Chinese and Western cultures.

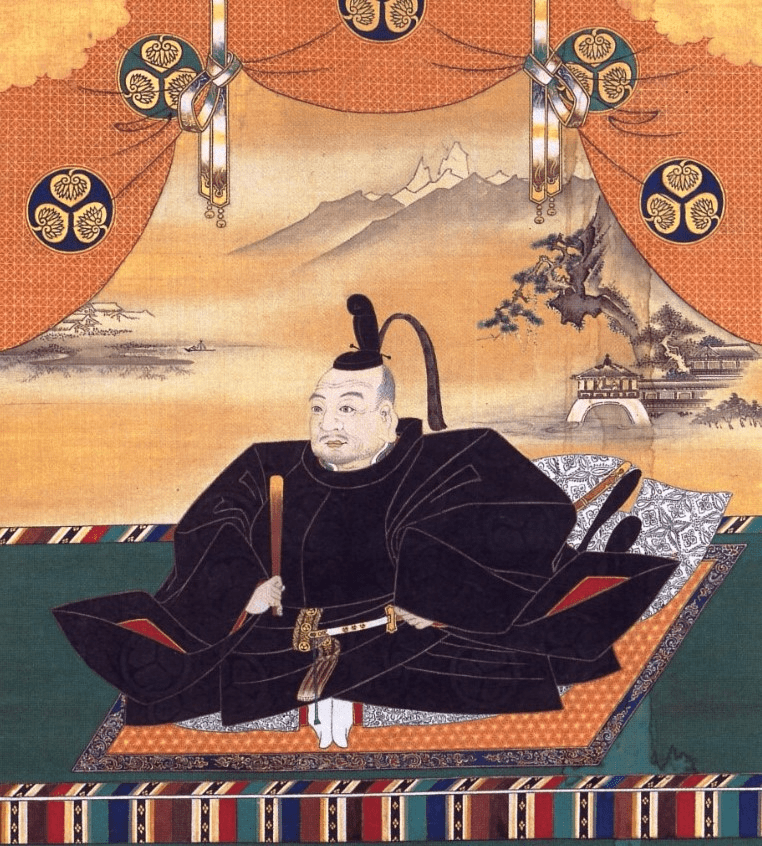

Edo period (1603 – 1868 a.C.)

The Edo period began with the establishment of the Tokugawa shogunate, which moved the capital to Edo (present-day Tokyo) and implemented a feudal system based on isolation, social hierarchy, and strict political control. This era was characterised by peace, stability, economic and population growth, as well as rigidity, censorship, and occasional social unrest. It saw the development of popular culture, ukiyo-e art, literature, and kabuki theatre.

During this time, Japan was ruled by the Tokugawa family, who centralised power under the shogunate, the supreme military authority. The first Tokugawa shōgun, Tokugawa Ieyasu, unified the feudal lords or daimyōs under his rule. Additionally, the last Tokugawa shōgun, Tokugawa Yoshinobu, resigned following the Boshin War, which was fought between supporters of the shogunate and those of the Meiji Emperor.

The Edo period was characterised by Japan’s isolation from the rest of the world, internal peace, economic and cultural development, and the prominence of the samurai class, who were loyal to the shōgun.

Meiji period (1868 – 1912 a.C.)

The Meiji period marked the restoration of imperial power and the opening of Japan to the world after over two centuries of isolation. This era was characterised by rapid modernisation, industrialisation, westernisation, and significant social, political, and cultural transformation. Feudalism and the shogunate were abolished, a new constitution was established, a national army was created, and advancements in education, science, and the arts were promoted.

During the Meiji period, Japan evolved from a feudal and isolated nation into a modern, westernised power. Under Emperor Meiji, who restored imperial authority following the end of the Tokugawa shogunate, Japan underwent profound changes. A new constitution was promulgated, a parliament was established, samurai privileges were abolished, industrialisation was accelerated, the military was modernized, and many elements of Western culture were adopted.

This period also saw the rise of Japanese nationalism and imperialist expansion in Asia, leading to conflicts with China and Russia. The name Meiji, meaning “Era of Enlightened Rule”, reflects the emperor’s goal to establish a centralised and legitimate government.

Taisho period (1912 – 1926 a.C.)

The Taisho period, coinciding with the reign of Emperor Taisho (Yoshihito), was brief and marked by the emperor’s mental illness. This period saw a short-lived flourishing of democracy, known as “Taisho Democracy,” as political power was ceded to the Japanese parliament due to the emperor’s health issues.

However, it was also a time of economic, social, and cultural crisis, which paved the way for the rise of militarism, ultra-nationalism, and totalitarianism in the subsequent Showa period.

Showa period (1926 – 1989 a.C.)

The Showa period, named after Emperor Hirohito (posthumously known as Emperor Showa), was one of the longest and most turbulent periods in Japanese history. Spanning over six decades, it was marked by the rise and fall of Japanese imperialism, the devastation of World War II, the American occupation, the post-war economic miracle, and the end of the Cold War.

The name Showa means “enlightened peace” or “Japanese glory”, reflecting the era’s ambitions and contradictions. Emperor Hirohito was a symbol of national unity and historical continuity, but he also had to adapt to the sweeping social and political changes that transformed Japan into a world power and then into a modern democracy.

Heisei period (1989 – 2019 a.C.)

The Heisei period, meaning “peace and harmony“, was named by Emperor Akihito, who succeeded his father, Emperor Hirohito (posthumously Emperor Showa). This era was characterised by Japan’s modernisation, globalisation, and cultural influence, but also faced significant economic, social, and environmental challenges.

Notable events included the bursting of the financial bubble and the subsequent “lost decade” of the 1990s, the 1995 Kobe earthquake, the 1995 sarin gas attack in the Tokyo subway by the Aum Shinrikyo cult, the 2011 Tohoku earthquake and tsunami and the Fukushima nuclear disaster, and Emperor Akihito’s abdication in 2019—the first in over two centuries. His abdication marked the beginning of the Reiwa period, with his son, Emperor Naruhito, ascending to the throne.

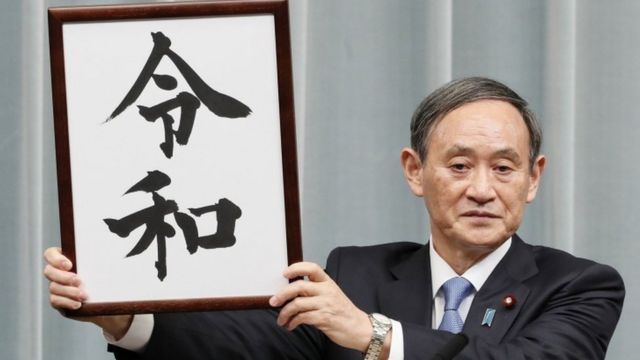

Reiwa period (2019 – Present)

The Reiwa period, beginning on May 1, 2019, after Emperor Akihito’s abdication, means “beautiful harmony” and was derived from a poem in the classic Man’yōshū anthology. Prime Minister Shinzo Abe noted that the new era name reflects Japan’s culture, traditions, and hopes for the future. The Reiwa period has been characterised by significant challenges, including the COVID-19 pandemic, the postponement and eventual hosting of the Tokyo 2020 Olympics, climate change, an aging population, and geopolitical tensions in Asia. Despite these challenges, the Reiwa period is also expected to be a time of technological innovation, social diversity, and cultural openness.

Japan in the contemporary world

Since the Meiji Restoration in 1868, Japan has undergone substantial political, cultural, and socio-economic transformations. One of the most pivotal events was World War II, which left the country devastated and its economy in shambles.

However, following a vigorous period of reconstruction driven by the government and the business sector, Japan emerged as an economic and technological powerhouse in the ensuing decades.

Post-world war II Japan: Reconstruction and socio-economic change

The end of World War II marked the beginning of a transformative era for Japan. U.S. occupation forces arrived on August 30, 1945, initiating a series of political and social reforms.

With the implementation of the Dodge Plan, Japan experienced remarkable economic growth from the 1950s to the 1970s, focusing on mass production and the export of electronics, automobiles, and machinery.

Politics and culture in the Heisei era

The Heisei era began in 1989 with Emperor Akihito’s succession and concluded in 2019 with his abdication in favor of his son, Naruhito. During these years, Japan saw significant changes across various domains. Politically, there was an evolution of traditional political parties, although the Liberal Democratic Party retained its dominant position for most of the era. Additionally, Japan faced major challenges, including natural disasters and an aging population.

Culturally, Japan continued to export its pop culture globally, achieving widespread success with manga, anime, and video games. Traditional arts such as the tea ceremony and kabuki, as well as other cultural practices, continued to thrive and attract international visitors, showcasing Japan’s rich cultural heritage.

Recommended tours to learn about Japanese history

If you’re interested in exploring Japan’s history firsthand, there are numerous sightseeing tours that offer a journey back to ancient Japan. Here are some recommended tours to delve into Japanese history through physical exploration:

- Todaiji temple (Nara). This temple is an iconic site from Japan’s Nara era. The main attraction is the Great Buddha Hall, which houses a 16-meter high bronze Buddha statue.

- Himeji castle. A feudal castle that has remained intact since the 17th century. Recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, offering insights into Japanese military architecture.

- Gion district (Kyoto). Famous during the Edo era for its geisha houses, today retains traditional buildings and people dressed in kimonos, providing a glimpse into historical Kyoto.

- Kiyomizudera temple (Kyoto). One of Japan’s oldest and most beautiful temples, situated on a hill with panoramic views of the city and surrounded by cherry trees.

- Kinkakuji temple (Kyoto). Also known as the Golden Pavilion, a stunning structure covered in gold that reflects its brilliance in the surrounding pond.

- Meiji shrine (Tokyo). Tokyo’s most important shrine, dedicated to Emperor Meiji and his wife, symbolising Japan’s modernisation.

- Itsukushima shrine (Miyajima). Located on a sacred island with its famous floating torii gate, designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

- Hiroshima Peace Memorial Park. Commemorates the victims of the 1945 atomic bombing, featuring the Atomic Bomb Dome, Peace Memorial Museum, Children’s Memorial, and Cenotaph, providing a poignant reminder of the impact of war and the pursuit of peace.

These are just a few of the many places in Japan where you can learn about its history, culture, and religion. We encourage you to explore them yourself and be amazed by the richness and diversity of this ancient country.